They raced on autobahn interchanges near Salzburg, on the flat-out speed course through the forests on the original Hockenheimring, on legendary traditional circuits like the Nürburgring and Monza, on airfields, military camps, country roads, village cobbles, and at one-bike-at-a-time hill climbs up mountain passes.

It is a world which survives only in old black-and-white photographs, and in the memories of the people who were there: the world of European motorcycle road-racing more than 50 years ago, in the 15 or so years after the end of World War Two.

This was racing far removed from the commercialised stadium contests of the modern Grands Prix. Photographs from these long-forgotten European public-road circuits show riders racing on town streets and country roads, past houses and stone walls, sometimes over cobblestones, sometimes with the crowd almost close enough to touch. An occasional banner may advertise oil or alcohol, but the only writing on the machines is the maker’s name on the fuel tank; the bikes are unstreamlined, and the riders wear pudding-basin helmets and plain black leathers. And among them, in photographs from Brno, Mulhouse or Villefranche-de-Rouergue, are helmets painted with a kangaroo; Australian riders, 18,000km from home.

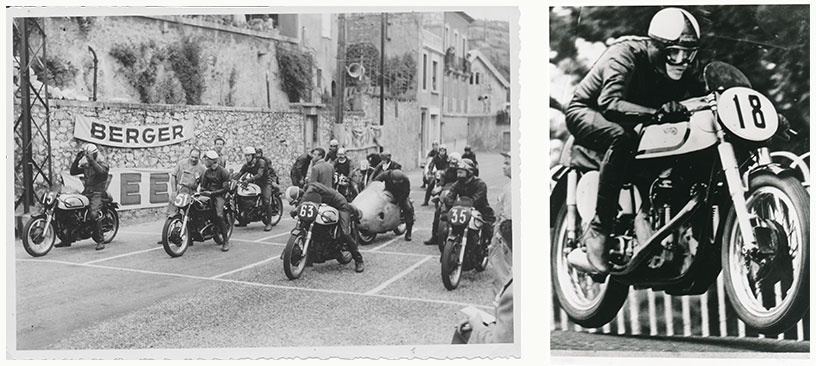

Left: The 350 front row: Jacques Collot (15), Auguste Goffin (51), John Storr (63) and Eddie Grant (35). Right: Race start on Allee Aristide Briand, one of the main streets of Villefranche-de-Rouergue in 1956.

Some of them had crossed the world because they had been chosen to officially represent Australia at the pinnacle of motorcycle road racing in the annual Tourist Trophy races in the Isle of Man. Some of them hoped they would display enough speed to be offered a ride with one of the factory teams. Others made the trip because they just wanted to race. They could do more racing in six months in Europe than they could in perhaps two years in Australia.

What was more, they would be paid to do it. Organisers of European motorcycle races offered cash – “starting money” – to attract riders to their meetings. If a rider, even a virtually unknown one, planned ahead and had reliable transport, lived modestly and avoided injury, he could race every weekend, sometimes mid-week as well, and expect to at least break even. It was unofficially known as the Continental Circus, a structure which had been evolving since before WW2 with most of the participating riders being European, but always with a few from afar.

Organisers of the major meetings tended to offer less starting money to lesser-known riders, because the factory teams and the leading riders would make up much of the field. Many smaller meetings, on the other hand, paid well because they were keen to attract entries, and a private entrant with some good results could negotiate an even better deal. So a rider could choose to either have his entry accepted for a major meeting, accept low starting money, and hope to catch the eye of a factory team, or pick one of the several provincial meetings that might be running on the same weekend and negotiate better starting money, and maybe earn some prize money as well.

The 1955 calendar of the Federation Internationale Motorcycliste* (the FIM, the sport’s governing body) provides a perfect illustration. In Europe that year it listed nine Grand Prix meetings which counted towards the world championships and four more Grands Prix which were non-championship events. But between March 31 and October 16 there were no fewer than 78 other meetings where international-licence riders – Australians, for example – could also compete. The difficulty, almost, was to decide where to race. On the May 1 weekend, for example, as well as the world championship Spanish Grand Prix round at Barcelona, there was the non-championship Austrian Grand Prix at Salzburg, and international-level meetings at Mettet in Belgium and Bourg-en-Bresse in France. There was even more choice the previous year, when the first weekend of May included Salzburg on the Saturday and five meetings on the Sunday: Floreffe, San Remo in Italy, St Wendel, Bourg-en-Bresse and Marseille. On weekends like these, promoters – particularly of meetings that were geographically close together – had to compete to attract the best drawcards.

A 1950s private entrant might fret if his season included less than 15 meetings. Ideally, he wanted to race every weekend throughout the season, with the occasional mid-week race as well. Most riders had two bikes, often a 350 and a 500, so they could compete in two classes at each event. After a Saturday meeting some would drive through the night, maybe even to another country to compete at their second race meeting on the one weekend.

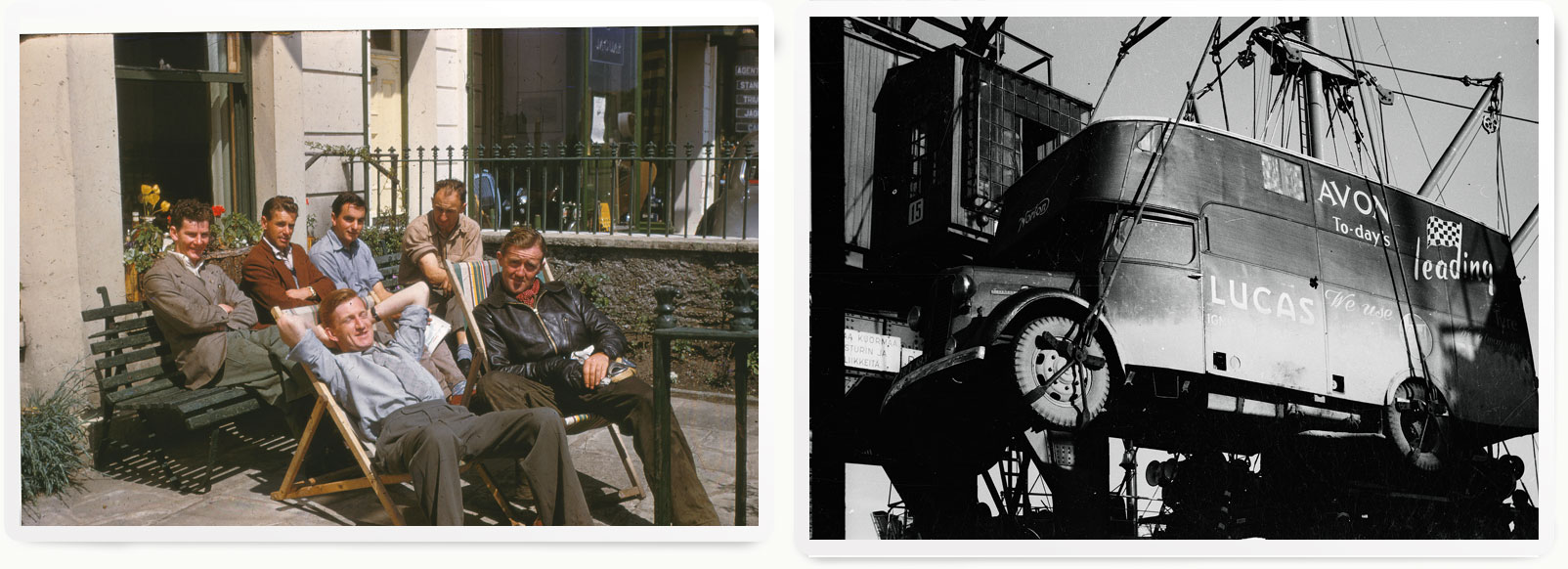

Left: The boys in the sun at Rosa Villa before the 1954 Isle of Man TT. Front row (L-R): Gordon Laing and Jack Ahearn. Second row (L-R): Maurie Quincey, unknown, Keith Campbell and Leo Simpson. Campbell was injured during practice and did not race. Right: Everything you own in the world hangs from that sling! Keith Campbell’s van at Turku docks in Finland.

They raced in every corner ofEurope, from the northern coast of Ireland at Portstewart, to Opatija on the Adriatic coast of what is now Croatia, to Hedemora, deep in the heart of Sweden. They raced on autobahn interchanges near Salzburg, on the flat-out speed course through the forests on the original Hockenheimring, on legendary traditional circuits like the Nürburgring and Monza, on airfields, military camps, country roads, village cobbles, and at one-bike-at-a-time hill climbs up mountain passes.

Crowds at the biggest 1950s meetings were truly massive, especially in Germany. There were 400,000 people at Solitude, near Stuttgart, for the West German Grand Prix in August 1951, when it wasn’t a world championship round. Germany had just been readmitted to international motorcycle sport, which meant international riders (including Ken Kavanagh) could compete there. That record crowd was bettered at Solitude in 1954, with half a million people attending the Grand Prix. Races at the Sachsenring in East Germany attracted well over a quarter of a million spectators every year. The 1958 Swedish Grand Prix meeting at Hedemora, its only year as a world championship round, was claimed to have brought a larger crowd than any other sporting event in Swedish history. Even the less famous events, once-a-year festivals in small mining or farming towns, might temporarily swell the population by a factor of five or six. Many Germans might never have heard of St Wendel or Schleiz, many Frenchmen might struggle to give you directions to Vesoul, but the private entrants knew the way, to good racing and good money.

Kel Carruthers, who started as a private entrant in Europe and went on to become 250cm³ World Champion, described his 1960s private-entrant experience in terms which would have been equally valid for the 1950s: “You worked for a different boss every week, and you worked on a different pay scale every week.” The rookies and strugglers sometimes had to survive on canned baked beans between meetings, and the really unsuccessful riders would go broke and have to find a job in a machine shop or a car factory to save the boat fare back to Australia. Successful riders could earn enough not to have to work during the off season.

One rider described it as a utopian existence. This was living; to be in your 20s, on the road in summertime Europe with one or two of your mates, or with your new wife, in a different town every week. And, after years spent persevering back home with old equipment, the excitement of riding new bikes bought direct from the British factories and being paid to do what you loved doing. In every sense, 1950s suburban Australia was a long way away.

This marked these adventurers as special, whether they were racers, mates, wives, or even the occasional Australian or New Zealand tourists who were offered transport with the racers. There were two cases in the 1950s where the traditions of the Continental Circus and the Antipodean “grand tour” of Europe overlapped. In 1955, Bob Brown had two Australian women as travelling companions on the Continent. Two years later, New Zealand’s Noel McCutcheon offered a lift to two women he met on the voyage from Wellington to London. The girls wanted to see Europe, McCutcheon had a van with four bunks and, in true 1950s style, they did the cooking.

None of these racers and tourists could ever have been accused of having “independent means”. They had all had to work and save to make the trip; they all had to have that spark of adventure and self-belief that launched them on a journey that would take them so far from home. So they were a select group; about 40 Australian and 30 New Zealand riders competed in Europe in the 1950s. Usually, the riders already at least knew each other from the Australian scene, but on the Continental Circus they formed their own community. In the European race meeting paddocks, which were sometimes literally a farmer’s paddock or a grassy town common, there might be as many as four vans with “Australia” painted next to the riders’ names, parked together, with washing hanging on makeshift lines between the vans and people having lunch on the grass. Counting wives and helpers, it would rarely add up to more than a dozen Australians.

But there was always a raw edge to the experience. The reality was that this was a dangerous game. One Australian reckoned he attended 15 funerals in his three years in Europe. Two New Zealand riders talked of the key reason why they left the Circus and never came back. For Noel McCutcheon at the end of 1958 and John Hempleman at the end of 1960, that reason was the death of the leading Australian rider of their day.

Even a common injury like a broken collar-bone, which today could be quickly repaired by pinning or plating, was likely to put a rider out for the balance of the season. If the injury was to a works rider, it might create a great opportunity for a private entrant to get a factory ride; but for the private entrant himself, injury could mean an early return home.

There could be a raw financial edge too. Riders would be promised start money, then after driving long distances to the circuit they would be told by the organisers that he had written to cancel their entry. Yet since they had arrived anyway, they could still race, but for no money. One Australian rider claims he hung a race organiser out his office window until he agreed to honour a start-money deal. Other organisers were quite the opposite, providing unexpected gifts as rewards for spirited rides, inviting Australian riders home for dinner.

The day-to-day world of the Circus was far from luxurious. A paddock area with running water was considered well-appointed, and the other side of life on the road was living out of a van for six weeks at a time, and travelling across a Europe where the boom of the post-war years was only just beginning. Mountain passes were still narrow, with unfenced sheer drops over the side, cities still pocked by bomb damage.

Political changes were coming too. Today the Iron Curtain is no more, Germany is unified, Czechoslovakia is two nations, the old Yugoslavia is half a dozen. In those days, Europe must have seemed like an endless succession of borders. In 1955, Keith Campbell was possibly the first Australian sports person to compete behind the Iron Curtain. Within a year, Australian and New Zealand private entrants were travelling into East Germany and Czechoslovakia two and three times a year, past minefields and machine-gun toting guards. Some autobahns in East Germany were still missing bridges destroyed in WW2.

Even the Suez Crisis in late 1956 reached the racing world. Australian riders on their way home through the canal remembered their ship being followed by guns on the shore, and for the 1957 season they travelled to Europe via Cape Town, to a Europe where petrol was rationed and some race meetings were cancelled due to fuel shortages.

Motorsport itself – four-wheeled racing, not motorcycling – also brought changes to the Continental Circus. The massive disaster during the 1955 24-hour car race at Le Mans (still the worst accident in motor-sport history with a driver and 82 spectators killed) brought a French government ban on racing on some (although not all) public roads and ended road racing for all time in Switzerland**. Then another accident involving spectator fatalities in Italy, during the 1957 Mille Miglia (a 1000-mile sports-car race from Brescia to Pescara, Rome, Florence and back to Brescia) ended racing on Italian public roads, including the Milan to Taranto motorcycle race, which ran virtually the length of Italy.

It is a very different Europe today, and racing is vastly different. It is not too hard to envisage many current Australian internationals following the Continental Circus had they been born 60 years earlier, because there isn’t much difference between the essential elements of a 1950s international and today’s racers. They’re all at their best on the bike; they all spend hours thinking about how to win the next race, and made the same sacrifices.

Left: Gwen Bryen enjoys the scenery at Lake Como, near the Moto Guzzi factory. Right: Yes, it is a paddock. A local school boy checks out the machines of Keith Campbell and Bob Brown at Schotten in 1955.

What has changed and what will never be the same is where they raced; the way they did it and the way they made a living. This story is generations away from modern motorcycle Grand Prix racing, and indeed from the experience of most Australians born after the 1950s.

It’s time their stories be told on two counts. Firstly, their exploits have remained largely invisible for six decades. Today, few Australian race enthusiasts could name our first world motorcycle Grand prix champion, Keith Campbell.

In the 1950s, Australia’s top athletes, Australian rules footballers, cricketers, golfers, rugby league players, swimmers and tennis players were household names, and Jack Brabham became one in 1959. The men in this book achieved many great things half a world away in relative anonymity and blazed a trail of toughness and endeavour for future generations of successful Australian riders to follow. But at the time those achievements went largely unrecognised outside the motorcycle community. There’s a stunning example of this lack of acknowledgement. In the summer of 1957-58, newly-crowned world 350 champion Campbell and new wife Geraldine visited the offices of a Melbourne newspaper for an interview. The story remained unpublished in the paper’s files until Campbell died in a racing accident in July 1958.

Secondly, their histories should be recorded because the memories are disappearing with the people who lived them, people who are now in their 70s and 80s. They might seem unremarkable sitting in their suburban lounge rooms or in their workshops. But then hear them talk of breath-crushing bumpy straights, narrow tree-lined country roads, treacherously slippery village streets, and their epic travels between meetings. Hear them remember. These men and women are inspiring.

* Renamed the Federation Internationale de Motorcyclisme in 1998.

** The Le Mans tragedy impacted on the Continental Circus for years. The French Grand Prix disappeared from the world championship calendar until 1959. The Swiss Grand Prix at Berne disappeared forever. The traditional August international races in France were not held in 1955. Some international road races disappeared, never to be run again.